Playing cards

may have been designed amid the Tang line around the ninth century AD because of the utilization of woodblock printing technology. The principal conceivable reference to card diversions originates from a ninth century content known as the Collection of Miscellanea at Duyang, composed by Tang administration author Su E. It portrays Princess Tongchang, girl of Emperor Yizong of Tang, playing the “leaf amusement” in 868 with individuals from the Wei faction, the group of the princess’ husband. The principal known book on the “leaf” diversion was known as the Yezi Gexi and supposedly composed by a Tang lady. It got analysis by authors of consequent dynasties. The Song line (960– 1279) researcher Ouyang Xiu (1007– 1072) attests that the “leaf” diversion existed at any rate since the mid-Tang administration and related its creation with the improvement of printed sheets as a composing medium. However, Ouyang additionally guarantees that the “leaves” were pages of a book utilized in a table game played with shakers, and that the tenets of the amusement were lost by 1067.

Different recreations spinning around hard drinking included utilizing playing cards of a sort from the Tang administration ahead. Be that as it may, these cards did not contain suits or numbers. Rather, they were printed with directions or relinquishes for whomever drew them.

The soonest dated example of a diversion including cards with suits and numerals happened on 17 July 1294 when “Yan Sengzhu and Zheng Pig-Dog were found playing cards [zhi pai] and that wood hinders for printing them had been appropriated, together with nine of the real cards.”

William Henry Wilkinson recommends that the primary cards may have been real paper money which served as both the instruments of gaming and the stakes being played for, like exchanging card recreations. Utilizing paper cash was awkward and hazardous so they were substituted by play cash known as “cash cards”. One of the most punctual recreations in which we realize the principles is madiao, a trap taking amusement, which dates to the Ming Dynasty (1368– 1644). fifteenth century researcher Lu Rong portrayed it is as being played with 38 “cash cards” isolated into four suits: 9 in coins, 9 in series of coins (which may have been misjudged as sticks from unrefined illustrations), 9 in bunches (of coins or of strings), and 11 of every many hordes (a heap is 10,000). The two last suits had Water Margin characters rather than pips on them :132 with Chinese characters to stamp their position and suit. The suit of coins is backward request with 9 of coins being the most minimal going up to 1 of coins as the high card.

Persia and Arabia playing cards

Regardless of the wide assortment of examples, the suits demonstrate a consistency of structure. Each suit contains twelve cards with the best two normally being the court cards of ruler and vizier and the last ten being pip cards. A large portion of the suits utilize switch positioning for their pip cards. There are numerous themes for the suit pips however some incorporate coins, clubs, containers, and swords which look like later Mamluk and Latin suits. Michael Dummett guessed that Mamluk cards may have slipped from a before deck which comprised of 48 cards isolated into four suits each with ten pip cards and two court cards.

Egypt playing cards

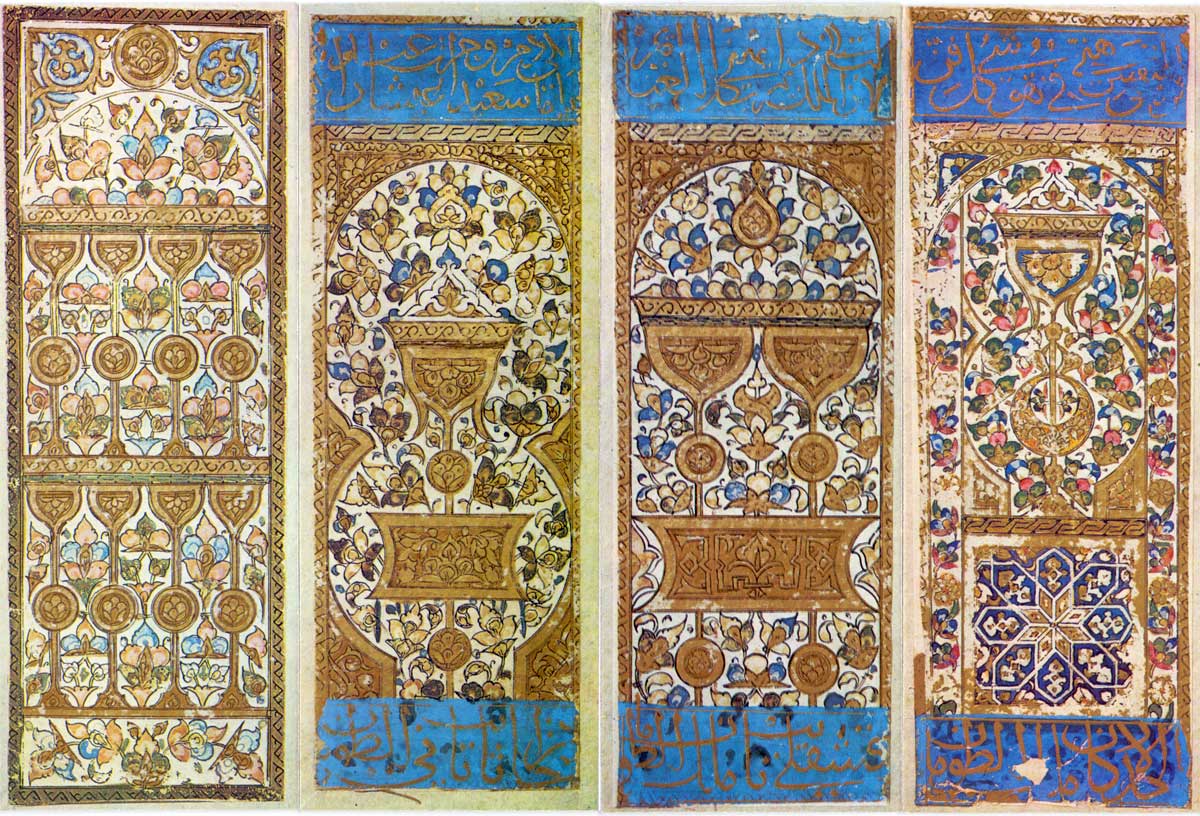

Four Mamluk playing cards.

By the eleventh century, playing cards were spreading all through the Asian mainland and later came into Egypt.:309 The most seasoned enduring cards on the planet are four pieces found in the Keir Collection and one in the Benaki Museum. They are dated to the twelfth and thirteenth hundreds of years (late Fatimid, Ayyubid, and early Mamluk periods).

A close total pack of Mamluk playing cards dating to the fifteenth century and of comparative appearance to the pieces above was found by Leo Aryeh Mayer in the Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, in 1939. It is certainly not a total set and is really made out of three unique packs, most likely to supplant missing cards. The Topkapı pack initially contained 52 cards including four suits: polo-sticks, coins, swords, and mugs. Each suit contained ten pip cards and three court cards, called malik (ruler), nā’ib malik (emissary or appointee lord), and thānī nā’ib (second or under-delegate). The thānī nā’ib is a non-existent title so it might not have been in the most punctual forms; without this position, the Mamluk suits would fundamentally be equivalent to a Ganjifa suit. Truth be told, “Kanjifah” shows up in Arabic on the lord of swords is as yet utilized in parts of the Middle East to depict current playing cards. Impact from further east can clarify why the Mamluks, the majority of whom were Central Asian Turkic Kipchaks, called their containers tuman which implies horde in Turkic, Mongolian and Jurchen languages.Wilkinson hypothesized that the mugs may have been gotten from rearranging the Chinese and Jurchen ideogram for heap (万).

The Mamluk court cards demonstrated conceptual plans or calligraphy not delineating people potentially because of religious prohibition in Sunni Islam, however they bore the positions on the cards. Nā’ib would be acquired into French (nahipi), Italian (naibi), and Spanish (naipes), the last word still in like manner utilization. Boards on the pip cards in two suits demonstrate they had an invert positioning, a component found in madiao, ganjifa, and old European card recreations like ombre, tarot, and maw.

A section of two whole sheets of Moorish-styled cards of a comparative however plainer style were found in Spain and dated to the mid fifteenth century.

Fare of these cards (from Cairo, Alexandria, and Damascus), stopped after the fall of the Mamluks in the sixteenth century. The guidelines to play these amusements are lost yet they are accepted to be plain trap diversions without

Spread crosswise over Europe and early structure changes

Four-suited playing cards are first bore witness to in Southern Europe in 1365, and are likely gotten from the Mamluk suits of containers, coins, swords, and polo-sticks, which are as yet utilized in conventional Latin decks. As polo was a dark game to Europeans at that point, the polo-sticks progressed toward becoming mallet or cudgels. Their essence is authenticated in Catalonia in 1371, 1377 in Switzerland, and 1380 in numerous areas including Florence and Paris. Wide utilization of playing cards in Europe can, with some assurance, be followed from 1377 onward.

In the record books of Johanna, Duchess of Brabant and Wenceslaus I, Duke of Luxembourg, a passage dated May 14, 1379 peruses: “Given to Monsieur and Madame four diminishes, two structures, esteem eight and a half moutons, wherewith to purchase a pack of cards”. In his book of records for 1392 or 1393, Charles or Charbot Poupart, treasurer of the family unit of Charles VI of France, records installment for the depiction of three arrangements of cards.

From around 1418 to 1450 expert card producers in Ulm, Nuremberg, and Augsburg made printed decks. Playing cards even contended with reverential pictures as the most widely recognized utilizations for woodcuts in this period. Most early woodcuts of different types were shaded in the wake of printing, either by hand or, from around 1450 onwards, stencils. These fifteenth century playing cards were presumably painted. The Flemish Hunting Deck, held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the most established finish set of conventional playing cards made in Europe from the fifteenth century.

As cards spread from Italy to Germanic nations, the Latin suits were supplanted with the suits of leaves (or shields), hearts (or roses), chimes, and oak seeds, and a blend of Latin and Germanic suit pictures and names brought about the French suits of trèfles (clovers), carreaux (tiles), cœurs (hearts), and arouses (pikes) around 1480. The trèfle (clover) was likely gotten from the oak seed and the provoke (pike) from the leaf of the German suits. The names provoke and spade, in any case, may have gotten from the sword (spade) of the Italian suits. In England, the French suits were in the end utilized, in spite of the fact that the most punctual packs circling may have had Latin suits. This may represent why the English called the clovers “clubs” and the pikes “spades”.

In the late fourteenth century, Europeans changed the Mamluk court cards to speak to European eminence and specialists. In a portrayal from 1377, the soonest courts were initially a situated “lord”, an upper marshal that held his suit image up, and a lower marshal that held it down. The last two compare with the ober and unter cards found in German and Swiss playing cards. The Italians and Iberians supplanted the Ober/Unter framework with the “Knight” and “Fante” or “Sota” before 1390, maybe to make the cards all the more outwardly recognizable. In England, the most minimal court card was known as the “heel” which initially implied male youngster (analyze German Knabe), so in this setting the character could speak to the “ruler”, child to the lord and ruler; the importance hireling created later.Queens showed up sporadically in packs as right on time as 1377, particularly in Germany. In spite of the fact that the Germans relinquished the ruler before the 1500s, the French for all time lifted it up and put it under the lord. Packs of 56 cards containing in each suit a ruler, ruler, knight, and blackguard (as in tarot) were once basic in the fifteenth century.

Amid the mid sixteenth century, Portuguese merchants acquainted playing cards with Japan. The primary indigenous Japanese deck was the Tenshō karuta named after the Tenshō period.